MULTI-LEVEL GOVERNANCE:

THE CASE OF THE ARGENTINE MODEL FOREST NETWORK

Monica Gabay[1]

Introduction

This paper presents the lessons of experience resulting from over ten years of work by the National Model Forest Program (NMFP) and the Argentine Model Forest Network (NMFN). The “model forest” concept implies a change in the traditional natural resources planning paradigm, since the leading role is assumed by the community, including marginalized stakeholders. This participatory planning process allows model forests to integrate and harmonize disperse initiatives at landscape scale, thus optimizing the outcomes.

In order to perform the analysis of the NMFP/NMFN, the author has adapted some of Dr. Yutaka Ohama’s conceptual framework of the “participatory local sustainable development” (PLSD) tools.

1. A nested network: multi-scale governance (local, national, regional, international)

Model forests networks, and the model forests themselves, involve multiple scales in terms of governance. From the local to the international level, each has a specific governance structure adapted to the needs and functions each organization performs. The scope of this paper is limited to governance structures at the local and national levels.

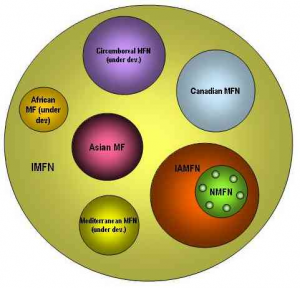

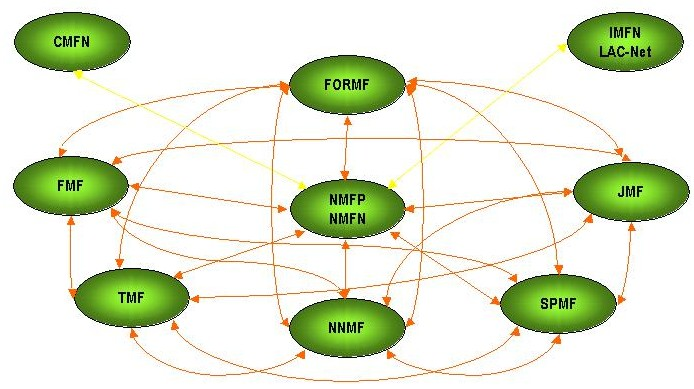

The basic unit of the network is the model forest, which is described below, and could be regarded as a local network of stakeholders with national and regional connections. As will be shown in this paper, at the national level, the Argentine network (NMFN) is formed by six model forests. The NMFN is one of the eleven members of the Iberoamerican Model Forest Network (IAMFN) which, in turn, is one of the six actual or developing networks that form the International Model Forest Network (IMFN). The diagram in Figure 1 shows the multi-scale nested networks.

Figure 1. Nested networks

2. The primordial building blocks: model forests

The model forest (MF) concept was created in Canada in 1991, as an answer to the growing conflicts arising between local communities and First Nations on one side, and forestry concessionaires on the other side. In the core of the problem was a strong difference in the stakeholders’ visions about development and sustainable development. The initiative was presented at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit[2], whereCanada assumed the compromise of disseminating this approach to sustainable forest management throughout the world. In 1994 the International Model Forest Network (IMFN) was established with three member countries:Canada,Mexico andRussia (IMFN, 2005).

In the heart of the model forest concept lies the notion of broad-based strategic partnership based on a large forested landscape.[3] It is interesting to note that the concept has evolved throughout the years and has widened its scope from the original narrow forestry focus to a broader perspective of sustainable local development. This means that the accent has moved from forest management innovative practices and techniques to a more inclusive view encompassing local communities and their environment. This evolution can be traced back to the inputs provided to the IMFNS by the Iberoamerican Model Forest Network (IAMFN), which has had a strong influence in the process of creating the framework document of principles and attributes[4].

There are six attributes that all the model forests in the world share, and provide the basis for networking:

- Partnership;

- Sustainability;

- Landscape;

- Governance;

- Program of activities;

- Knowledge-sharing, capacity building and networking.

The adoption of this philosophy involves a change in the traditional natural resources planning paradigm, since the leading role is assumed by the community, including marginalised stakeholders. Indeed, model forests are actual multisectorial strategic partnerships focused in conflict resolution and local sustainable development promotion based in inclusive planning and management with full participation of key stakeholders. These include, among others, the public sector, grassroots organizations, NGOs, private enterprises, rural producers, aboriginals, schools, research institutions, and universities.

The participatory planning process allows model forests to integrate and harmonize disperse initiatives within a defined area (landscape scale), and optimize the outcomes. The model forest thus becomes a fundamental tool for realizing the notion of sustainable development in the field, giving the forest inhabitants alternatives for sustainable forest management that make it possible for them to enhance their livelihoods.

Networking at national, regional and international levels strengthens model forest capacities through the exchange of knowledge and experiences, as well as horizontal cooperation. These nested networks involve governance structures designed to represent the key stakeholders for each level.

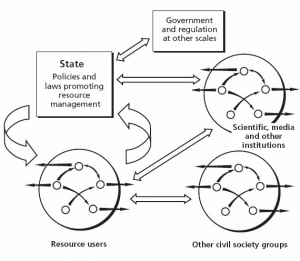

Figure 2. Cross-scale transversal linkages present in model forests.

Source: Adger et al. (2005).

Figure 2 shows the cross-scale transversal linkages within model forests, that encompass actors from the public sector organizations at different levels, natural resources users, civil society organizations, and the academia. This diversity and interactions present at the model forest sites are also present at the national and regional network levels, as will be presented below.

The governance structure of a model forest inArgentinais a board formed by representatives from key stakeholders who are appointed by consensus of all the partners. It is expected –and generally verified- that the board includes representatives from all the sectors involved in local sustainable development (e.g. local and provincial government, grassroots and community organizations, aboriginal groups, research organizations and universities, etc.).

3. The Argentine case: National Model Forest Program (NMFP) and Network (NMFN)

InArgentina, especially after the 1987 Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (a.k.a. the “Brundtland Report”), a strong evolution occurred in the federal forest policy, towards the implementation of a real participatory approach to forest management. The “Forest Principles” and Agenda 21 produced as a result of the 1992 Earth Summit engendered certain compromises to fulfill. However enticing the concept of sustainable development was, it was certainly difficult to translate it into concrete action. There was a need to create a new way of designing and implementing policies in order to achieve sustainable development.

The news of the creation of the IMFN and the establishment of the IMFN Secretariat (IMFNS) in 1995 reachedArgentinawith an excellent timing. The Directorate of Forestry initiated contacts and, as a result, the first workshop on model forests took place in early 1996. The workshop convened key stakeholders from all over the country. This broad-based workshop reached a consensus and proposed to adopt the model forest concept inArgentina. As a result,Argentina’s Model Forest Program (NMFP) was launched in May 1996, following an agreement signed between the Secretary of the Environment and Sustainable Development and the IMFNS, based inOttawa.

It should be emphasized that in the case ofArgentina, the implementation of the model forest concept was not a donor-driven initiative but an autonomous decision, for no financial support was received from either the IMFN or the Canadian government for the establishment of the NMFP or the creation of model forests. As for the technical support, it was limited to the participation of IMFNS officials at the first workshop and the provision of some technical documents produced by the Canadian Model Forest Program (CMFP) of the Canadian Forest Service (CFS).

Throughout its eleven years of history, the NMFP has undergone a profound evolution. The institutional and political changes in the Secretariat of the Environment and Sustainable Development, the birth of the National Model Forest Network (NMFN) in 2000 and its subsequent expansion, and the increasingly important role of the program at the regional and international levels, are among the key factors that have contributed to shape the current vision, objectives and strategies of the NMFP.

At its beginnings in 1996, the program replicated the Canadian Model Forest Program. A competitive process was launched for the selection of model forests proposals with a target of having one model forest per forest region. However, unlike the Canadian experience, there was no provision of subsidies for the emerging model forests. That meant that aspiring model forests had to provide for their own operational expenses and project investments.

The NMFP carried out a strong information campaign aimed at promoting the concept in the provinces with native forests. This effort produced mixed results, with only one formally approved model forest, and a number of initiatives under development by the year 2000.

Part of the explanation could be found in the fact that most Argentine provinces had little experience in the participatory approach. Besides, the fact that the NMFP was not providing funds to finance model forests made it less attractive in the view of the local authorities. A third important root-cause is the culture of local politicians, who tend to foster a situation of dependence of local communities as a means for political power.

The development of a model forest is a complex process that demands continuous efforts from the stakeholders as well as certain capacities for conflict management, organizational design and management, strategic planning, resource mobilization, among others. It also involves a period of time that usually exceeds the term of any local government.

In spite of these factors, during the last three years the author has noticed an increasing interest in the model forest concept from local governments at the municipal level. Two new model forests are currently under development as a result of the local government’s initiative, that was backed by the local community and grassroots organizations, as well as by the academia.

In sum, analyzing the twelve years of the NMFP, three distinctive periods can be identified as follows:

ü The first five years (1996 – 2000) have been mostly focused on the internal sphere, i.e. linkages with the “outside world” (namely, the IMFN, other countries) were weak, and no real networking activities were conducted. The NMFP devoted its resources to the promotion of the concept within the national borders, visiting provincial authorities and universities to show the advantages of the model forest concept for sustainable local development.

ü The second period (2001 – 2003) marks an opening to the “outside world”, and the start of some networking, particularly at the regional level with the creation of the Iberoamerican Model Forest Network (IAMFN)[5], of whichArgentina was a founding member. At the same time, the NMFP fostered the creation of the National Model Forest Network (NMFN) following the Canadian example. Model forests were much focused in their own creation and little attention was paid to national networking activities.

ü The current period (2004 – 2008) shows a strong expansion in regional and international networking, as well as the start of more fluid networking within the NMFN. The oldest Argentine model forests start looking outside their boundaries and collaborate among each other. Communications become more fluid within the NMFN. The NMFP starts developing collaborative relations with other countries’ programs and networks. Concrete joint actions are carried out as a result of regional and international networking. The NMFP plays a leading role in the IAMFN and the NMFN is the largest in the region.

3.1. Organizational design

The NMFP’s mission is to promote sustainable forest ecosystems management based on strategic partnerships between key stakeholders and networking, in order to contribute to local communities’ progress, considering social fairness, local needs and global concerns. The NMFP`s vision is to play a regional leadership role in implementing sustainable development initiatives through innovative strategies that encourage local stakeholders’ partnerships and adaptive co-management of natural resources.

The NMFP is part of the Directorate of Forestry – Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development. It is a flexible, horizontal, and small multidisciplinary team with one coordinator. The internal culture could be described as a “task” or Athena culture (Handy, 1995): a highly dynamic, problem-solving, team oriented culture with an emphasis on expertise and achievement rather than formal organizational structure and status. The NMFP is the Argentine focal point of the IMFN and LAC-Net, and is responsible for the coordination of the NMFN.

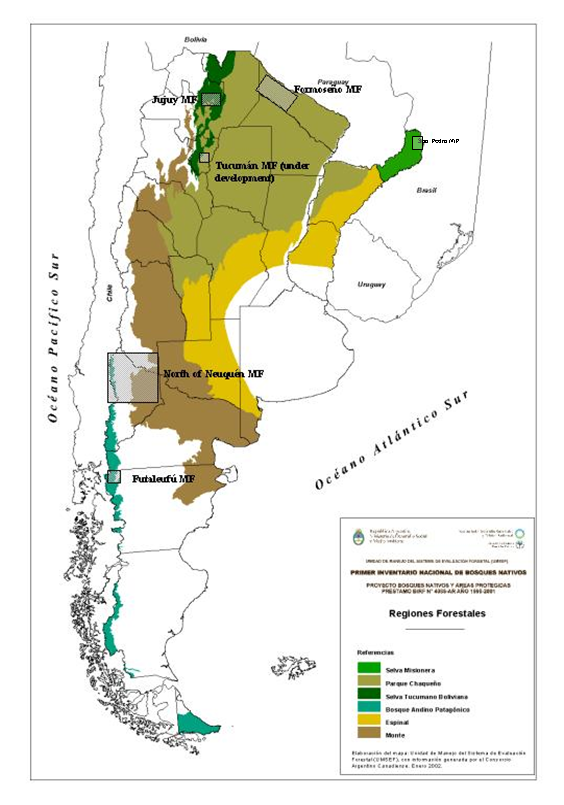

The NMFN currently comprises five active model forests, and a new site under development, namely: FormoseñoModelForest(800,000ha); FutaleufuModelForest(738,000ha); JujuyModelForest(130,000ha); Norte del Neuquen Model Forest (1,500,000ha); San Pedro Model Forest (443,500ha); and TucumanModelForest(under development)[6].

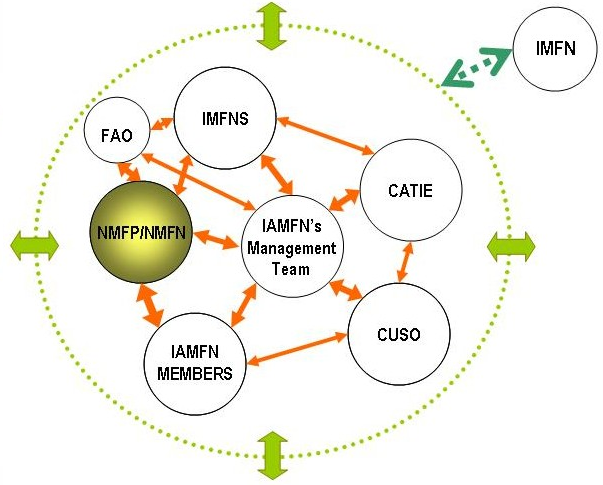

The NMFP/NMFN organizational structure is displayed in Figure 3. The arrows show the flows of communications, knowledge-sharing, and influence. There is a dialectical relationship of co-learning between the NMFP and the Argentine model forests through the exchange of information and an informal process of co-creation of policies at the federal level. This virtuous circle needs strengthening in order to live up to its true potential, for the model forests are not as old as the NMFP and they need to further develop their capacities.

The NMFN has the following functions:

i) Promote a fluid exchange of knowledge and experiences on sustainable forest management among Argentine and foreign model forest.

ii) Develop sustainable forest management criteria and indicators for their implementation in Argentine model forests, considering the country’s international commitments.

iii) Foster technical cooperation with other national and regional networks, and the International Model Forest Network.

iv) Impulse joint activities, particularly those related to sustainable forest management.

The NMFN has a board that includes representatives from all the model forests, plus the national coordinator of the NMFP. The board sets priorities for action, identifies key areas of interest for capacity building, strengthens linkages among the model forests, and defines positions regarding regional and international network matters.

Figure 4 shows the relative position of the NMFP/NMFN within the context of the Iberoamerican Model Forest Network (IAMFN), and linkages and flows of influence and communications between the different stakeholders.

The dotted circle represents the outer boundaries of the IAMFN. The green arrows show the flows of the IAMFN system with the exterior. The IMFN Secretariat (IMFNS) is a member of the board of the IAMFN, and conversely the IAMFN has one representative on the IMFN’s board. The length of the arrows shows the “social distance” between organizations, while the thickness of the arrows shows the strength of the interactions.

3.2. Stakeholders’ analysis

The NMFP/NMFN involves stakeholders from the public sector, private sector, grassroots and civil society organizations, multisectorial and international organizations, and the academia. Figure 4 classifies stakeholders according to whether they have a direct or indirect relation with or interest on the NMFP/NMFN, and whether they are internal or external to the NMFP/NMFN.

»]![Figure 4. Stakeholders analysis[7] Figure 4. Stakeholders analysis[7]](http://www.ianamericas.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/pic5.png) The stakeholders’ analysis presented in this matrix is done according to their relationships with the NMFP/NMFN, using the latter organization’s perspective. The stakeholders are classified into direct and indirect according to their degree of active involvement in the NMFP/NMFN initiatives, regardless of their degree of participation in the individual MF and of their being beneficiaries of projects; and into internal or external according to whether they are members of the NMFP/NMFN or not. Quadrant I shows those stakeholders that are members of the NMFP/NMFN and are very involved in the NMFP/NMFN activities. Quadrant II presents those stakeholders that are members of the NMFP/NMFN and are less involved in the NMFP/NMFN. QuadrantIIIdisplays those stakeholders that, in spite of not being members of the NMFP/NMFN, have a considerable degree of involvement/influence in the NMFP/NMFN activities. Quadrant IV exhibits those stakeholders that are not members of the NMFP/NMFN and are not involved in the NMFP/NMFN activities.

The stakeholders’ analysis presented in this matrix is done according to their relationships with the NMFP/NMFN, using the latter organization’s perspective. The stakeholders are classified into direct and indirect according to their degree of active involvement in the NMFP/NMFN initiatives, regardless of their degree of participation in the individual MF and of their being beneficiaries of projects; and into internal or external according to whether they are members of the NMFP/NMFN or not. Quadrant I shows those stakeholders that are members of the NMFP/NMFN and are very involved in the NMFP/NMFN activities. Quadrant II presents those stakeholders that are members of the NMFP/NMFN and are less involved in the NMFP/NMFN. QuadrantIIIdisplays those stakeholders that, in spite of not being members of the NMFP/NMFN, have a considerable degree of involvement/influence in the NMFP/NMFN activities. Quadrant IV exhibits those stakeholders that are not members of the NMFP/NMFN and are not involved in the NMFP/NMFN activities.

4. Some lessons of experience

Along the twelve years of existence of the NMFP, some valuable lessons have been learned concerning the creation and development of model forests based on the participatory approach, which are shared in this section.

One important lesson is that not all the initiatives are successful. Indeed, many proposals were abandoned at different points of their development for a number or reasons, including: lack of adoption of the model forest attributes; confusing the model forest concept with an environmentalist NGO; the insufficiency of social capital; radical political changes; lack of local authorities support; lack of minimum financial support.

The participatory nature of the process involved in the creation of a model forest implied somewhat long processes in order to develop these local networks. Part of the explanation for this can be found in the fact that stakeholders involved in the process usually have divergent and/or conflicting interests, and they have to achieve certain consensus regarding a shared vision, strategic objectives and goals,

At first glance, the transaction costs[8] involved in the process are higher than those involved in top down plans, program and projects. However true this could be for the ex ante costs related to the elaboration and presentation of a model forest proposal, the ex post costs (sustainable management and monitoring of the system) are usually lower, as demonstrated by the Canadian Model Forest Network experience (Canadian Model Forest Network, 2006).

The strong compromise and diversity of stakeholders involved in the Argentine model forests has allowed them to overcome political changes and economic crises. This demonstrates the importance of constructing networks of trust, consolidating local social capital and strengthening the governance architecture.

The model forest concept in Argentinahas a strong human development component. As such, a particularly relevant feature is social inclusion, empowering vulnerable groups, rural women and aboriginals to become protagonists of local endogenous development processes. Argentine model forests have successfully implemented projects[9] promoted by these stakeholders, with a focus in capacity building, education, strengthening productive development, and traditional knowledge.

Model forests have also generated valuable experiences related to the improvement of governance and conflict management, allowing for traditionally antagonists to work together in sustainable production initiatives.

Finally, the involvement of universities and research organizations in the Argentine model forests has proved most valuable in order to support model forest and local initiatives, proposing best practices and innovations for local development.

Conclusion

Model forests inArgentinahave proved to be more effective and efficient than traditional top down schemes in order to foster sustainable local development. They are strong learning and adaptive networks, allowing for the participation a diversity of stakeholders, including vulnerable and marginalized groups.

Model forests are also good tools for conflict management, although they require higher investments in terms of time and efforts in their early development stages.

Finally, model forests provide a territorial scale (landscape) that is adequate for experimentation and innovation.

References

CANADIAN FORESTSERVICE, 2003. Advancing Sustainable Forest Management from the Ground Up. Natural ResourcesCanada,Ottawa,Canada.

CANADIAN MODEL FORESTNETWORK. 2006. Achievements, Natural ResourcesCanada,Ottawa,Canada.

HANDY, Charles B., 1995. The Gods of Management: the changing work of organizations.OxfordUniversityPress,US.

IMFN, 2005. Partnerships to Success in Sustainable Forest Management. IDRC, Ottawa. Available on-line at: http://www.idrc.ca/uploads/user-S/11301799781Partnerships_to_Success.pdf (accessed:01/10/2007).

SHARMA, P.N., OHAMA, Y., 2007. Participatory Local Social Development – An Emerging Discipline. Bharat Book Centre,Lucknow,India.

ADGER, W.N., BROWN, K., TOMPKINS, E.L.. 2005. “The political economy of cross-scale networks in resource co-management”. Ecology and Society 10(2):9 [on-line]

http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol10/iss2/art9/ (accessed:10/22/2005)

IMFN. 2004. “Sembrando las semillas para un futuro sustentable”. IDRC, Ottawa, Canadá.

KUPERAN, K., POMMEROY, R.S., MUSTAPHA, N., ABDULLAH, R., GENIO, E., SALAMANCA, A.. sin fecha. “Measuring Transaction Costs of Fisheries Co-Management”. [on line] http://www.indiana.edu/~iascp/Drafts/kuperan.pdf (accessed:10/29/2005).

SAyDS. 1996-2004. “Guía para la Formulación de Propuestas de Bosques Modelo en la República Argentina”. Dirección de Bosques – Programa Nacional de Bosques Modelo, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

SRIBM/SRNyAH-DB/PRODIA. 1996. Informe del Primer Taller para la Red de Bosques Modelo en la República Argentina, Secretaría Internacional de Bosques Modelo, Secretaría de Recursos Naturales y Ambiente Humano – Dirección de Recursos Forestales Nativos, Programa de Desarrollo Institucional Ambiental SRNyAH/BID, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

UNITED NATIONS. 1972. “Declaración de la Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Medio Humano”. Available on line at::

http://www.unep.org/Documents.multilingual/Default.asp?DocumentID=97&ArticleID=1503&l=en (accessed:12/17/2005).

UNITED NATIONS. 1992. “Declaración Autorizada, sin Fuerza Jurídica Obligatoria, de Principios para un Consenso Mundial respecto de la Ordenación, la Conservación y el Desarrollo Sostenible de los Bosques de Todo Tipo”, en Informe de la Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre Ambiente y Desarrollo, Asamblea General A/CONF.151/26 (Vol.III). Disponible on-line en:

http://www.un.org/documents/ga/conf151/spanish/aconf15126-3annex3s.htm (accessed:12/17/2005).

WILLIAMSON, O.E.. 1985. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism: Firms, Markets, Relational Contracting. Macmillan, Nueva York, USA. Quoted in Kuperan et al. (s/f).

WILSON, B.. 2005. Conferencia sobre “Oportunidades para la región en materia forestal: Soluciones estratégicas – La experiencia canadiense” citada en “Canadienses promueven articulación técnica y comercial con Argentina”, Argentina Forestal.com 24:12-14.

WORLD COMMISSION ON ENVIRONMENT ANDDEVELOPMENT. 1987. Our Common Future.OxfordUniversity Press,Oxford,United Kingdom.

ANNEX 1 – LOCATION OF ARGENTINE MODEL FORESTS

Source: NMFP on a map produced by the UMSEF – Directorate of Forestry – Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development.

ANNEX 2 – NMFN STAKEHOLDERS ANALISYS[10]

|

ID |

STAKEHOLDER |

SECTOR |

GEOGRAPHICAL UNIT |

|

1 |

Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development | Public (Government) | Federal |

|

2 |

National Parks Administration | Public (Government) | Federal; also acts “local” because each national park has a certain degree of autonomy in its management. |

|

3 |

National Institute of Agricultural Technology | Public (Research & Extension) | Federal, but acts “local” for it is the local branches that participate in the NMFP/NMFN. |

|

4 |

National Universities | Public (Academia) | Federal (legally), but “local” in practice. |

|

5 |

Ministry of Foreign Relations, International Commerce and Cult | Public (Government) | Federal |

|

6 |

National programs development programs aimed at local communities (that are members of a MF) | Public (development projects) | Federal; most have decentralized execution. |

|

7 |

International projects working on environmental issues (“green” area) | Public (sustainable development projects) | International or bilateral + federal + provincial |

|

8 |

Other national organizations | Public (Government) | Federal |

|

9 |

Provincial government (ministries, secretariats, and directorates participating in MF activities) | Public (Government) | Provincial |

|

10 |

Andean – PatagonicCenterofForestryResearch and Extension | Public (Research & extension) | Regional (five patagonic provinces) |

|

11 |

Man and Biosphere (MAB) sites | Multisectorial partnerships | Provincial/local |

|

12 |

Irrigation organizations | Assets management (producers’ consortium) & public interest (public regulation + public property) | Provincial; usually associated to a river basin |

|

13 |

Inter-municipal entities | Public (Government) | Provincial |

|

14 |

Municipal Government | Public (Government) | Municipal |

|

15 |

Local chambers of commerce | Private (advocacy oriented) | Municipal |

|

16 |

Rural producers’ organizations | Private (advocacy oriented + mutual support + assets management) | Municipal; occasionally provincial |

|

17 |

Rural producers’ cooperatives | Private (common/group resource management for surplus generation) | Municipal |

|

18 |

Rural producers acting as individuals | Grassroots | Community |

|

19 |

Original peoples’ communities | Grassroots (mutual support + resource pool + assets management) | Community |

|

20 |

Education workers (inspectors, teachers, etc) | Public (Education) | Municipal/provincial |

|

21 |

NGOs, NPOs | Civil society organizations | Provincial/Municipal/Community |

|

22 |

Local community groups | Grassroots | Community |

|

23 |

Students (internships, volunteer work) | Civil society | Community |

|

24 |

LAC-Net | Multisectorial partnership | Regional (multilateral) |

|

25 |

IMFN | Multisectorial partnership | International (multilateral) |

|

26 |

FAO | International organization | International (multilateral) |

|

27 |

GEF | International organization | International (multilateral) |

|

28 |

CATIE | International organization | International (multilateral) |

|

29 |

IUFRO | International research network | International (multilateral) |

|

30 |

Bilateral cooperation agencies & embassies | Public (ODAs & donor countries) | Foreign governments (bilateral cooperation) |

|

31 |

World Bank | International organization | International (multilateral) |

|

32 |

CanadianForestService | Public (Government) | Federal in their country (foreign government) |

|

33 |

CanadianModelForestNetwork | Private (NPO); multisectorial partnership | National in their country (foreign NPO) |

|

34 |

Chilean MFs | Multisectorial partnerships | Local in their country (foreign partnerships) |

|

35 |

Castilla and Leon (Consejeria de Medio Ambiente) | Public (Government) | Autonomous region in their country (foreign government) |

[1] National Coordinator – National Model Forest Program and Network, Directorate of Forestry, Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development, Argentina. Alternate Director for Argentina at the Iberoamerican Model Forest Network. Adjunct Professor of “Administrative Law I” and “Administrative Law II” at the Faculty of Juridical and Political Sciences – Universidad del Museo Social Argentino. E-mail: mgabay@ambiente.gov.ar. URL: http://www.ambiente.gov.ar/bosques_modelo.

[2] The 1992 UN Earth Summit also produced the “Forest Principles” document, incorporating guidelines for the conservation and sustainable development of all the forests in the world.

[3] According to the IMFNS, “a model forest is both a geographic area and a specific partnership-based approach to sustainable forest management (SFM). Geographically, a model forest must encompass a land-base large enough to represent all of the forest’s uses and values-it is a fully working landscape of forests and farms, protected areas, rivers and towns. A model forest is also a voluntary, partnership-based approach for moving toward SFM. Because forests and people cannot be separated, people are at the heart of the model forest concept. They are the key factor in the search to define sustainability at the local level where model forests are rooted. A model forest partnership fully represents the environmental, social and economic forces at play within the land-base.” (on-line at: www.imfn.net. Last checked:10/01/2007).

[4] There is an on-going consultation process regarding the principles and attributes of model forests.

[5]FormerRegionalModelForest Network for Latin America and theCaribbean (LAC-Net).

[6] The location of the model forests is presented in a map of the NMFN on Annex 1.

[7] Public sector stakeholders are shown in yellow. Multisectorial stakeholders are shown in orange. International stakeholders are shown in green. Private sector stakeholders are shown in blue. Grassroots and civil society organizations are shown in pink. Assets management organization is shown in violet. The numbers correspond to the stakeholders’ ID as assigned in the table in Annex 2.

[8] Kuperan et al. (s/f), following Williamson (1985), classify collaborative management transaction costs in: i) information costs; ii) decision making costs; iii) collective operational costs; where the first two are ex ante and the last one is ex post.

[9] For further information, please refer to the NMFN’s website: www.ambiente.gov.ar/bosques_modelo.

[10] It should be noted that for the sake of simplicity, most stakeholders have been grouped under a global designation (e.g. “producers organizations”).

Hello. splendid job. I did not expect this. This is a impressive story. Thanks!

I love your Blog, it’s nice when you can tell somebody actuallly puts effort into a blog, and gives the blogs value.